(Download) "Wonder Tales from Baltic Wizards" by Frances Jenkins Olcott ~ eBook PDF Kindle ePub Free

eBook details

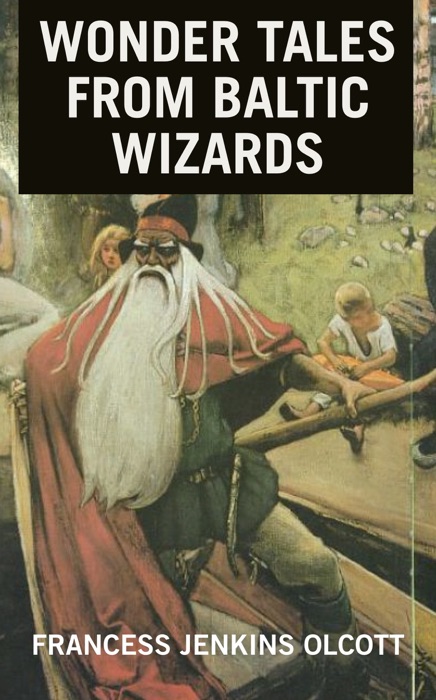

- Title: Wonder Tales from Baltic Wizards

- Author : Frances Jenkins Olcott

- Release Date : January 17, 2015

- Genre: Social Science,Books,Nonfiction,

- Pages : * pages

- Size : 237 KB

Description

ENCHANTMENTS, Wizards, Witches, Magic Spells, Nixy Queens, Giants, Fairy White Reindeer, and glittering Treasures flourish in these tales from the Baltic Lands—Lapland (both Finnish and Scandinavian), Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

And their setting is the Long Winter Night with its brilliant play of Northern Lights over the snow-covered tundra; or the brief Arctic summer—its sun burning night and day—with its birds, flowers, insect-clouds, singing waters, and almost tropic heat; or the golden sunshine of the southern amber coast.

But it is the Northern Lights themselves, flashing and flaming through the dark heavens, that cast their mystic weirdness over many of these tales molded by the peculiar imagination of the Asiatic and European East Baltic folks.

The farther our stories draw south from Lapland, the lower sink the Northern Lights, and the less their influence on folk-tales, till at last they merge with the warmer lights of Lithuania the amber-land. Wizards and wizardry abound in Lappish, Finnish, and Estonian tales, Witches appear more often in Latvian and Lithuanian ones. And in all these countries except Lapland, many European folk-tale themes, which we know in the Grimm collection, are found in new forms.

The Latvians and Lithuanians are Aryan peoples. The Lapps came from Asia, and the Finns and Estonians are descendants of the Finno-Ugric tribes emigrating from Asia to the Baltic shores. The Lapps and Finns are famous for their Wizards and wizardry. Even today some Lapps use magic incantations which are peculiar admixtures of ancient heathen superstitions and Christian ideas. The modern Lapp who is only half taught in the Gospel of Christ the Lord, which frees from superstition, is a strange compound of heathen survivals accentuated by the hard conditions of life within the Arctic Circle.

And bound by chains of superstition, the Lapp shows little progress. He is gradually being absorbed by neighboring races. It is far different with the Finns. Naturally more progressive, in co-operation with their compatriots, the Swedish-Finlanders, they have produced a modern Republic which in progress and culture is comparable to any European state. United with Finland is a large part of Lapland. Estonia, too, is a progressive modern Republic, as are Latvia and Lithuania.

But to return to Wizards in folk-lore. It is surprising that such an entertaining type of wonder tale as “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp,” which delights our children’s fancy, should have its roots in one of the most repellent of soul-slaveries—Shamanism.

The shaman, wizard, witch-doctor, heathen priest, medicine man—by whatever name he be called—was and still is among some heathen tribes a force controlling with iron grip tribal life, both of chiefs and people. By of his art, the shaman, usually a professional trickster, works on the fear, credulity, and natural religious instinct of his ignorant dupes.

By howlings and whistlings, hideous maskings, capers and leapings, beating of gongs and drums, incantations to bad or good spirits, and by hocus-pocus healing and some real curative knowledge, the shaman manages to keep the helpless folk in trembling terror of his power over their lives. He is an enemy to progress and civilization.

Shamanism in some form is prevalent in all parts of the world, among Asiatics, European Arctic peoples, Africans, American Indians including Eskimos, also Afro-Americans, and the savage islanders of the seas. It is not possible in this short Foreword, to discuss Shamanism in all its phases, with its holdover in mediaeval and modern witchcraft revivals.

But, just as many delightful poetic fairy tales have had their beginnings in pagan myths, so from professional wizardry have descended a variety and host of fascinating tales which, under the magic brush of a light and playful fancy, have taken on the colors of wonder to delight modern children.

The selections in this book come from German and English sources. There is a mass of East Baltic folk-lore and folk-tales in these languages, from which to choose. In the languages of Finland and Estonia alone, may be found more than 33,000 native folk-melodies, 55,000 folk tales, 125,000 riddles, 135,000 superstitions, 215,000 proverbs, 200,000 folk songs. This gives but a feeble idea of the extent of Baltic folk-lore.

The racial groupings of tales here, are interesting to compare—primitive Lapp legends; richly poetic creations of the Finns and their kindred, the Estonians; European types of wonder story, product of the Aryan Letts and Lithuanians. Each group holds its distinctive place in the history of peoples.

And what a variety of selections is here!—prose epitomes of the musical hero tales, and imaginative wonder stories of Finland and Estonia; weird Lapp ideas; romantic legends and wonder tales from Latvia and Lithuania, all so delightful to children. Repulsive tales have been omitted. The wonder tales, with few exceptions, are literally translated. Several rambling ones are shortened. The article, “What Happened to Some Lapp Children,” is composed of bits of assembled folklore. The half-title original verses are in Kalevala metre, while the little connecting stories, also original, follow the changing seasons of Lapland, and are woven from bits of folk-wisdom and custom.

All these colorful tales, together with The Tiny History of the Baltic Sea, and The Tiny Dictionary of Strange East Baltic Things will, we hope, charm the children and help them to understand and like the countries and peoples of our East Baltic neighbors.